Macro Notes - It’s Not QE: A Simple Explanation of Why the Fed is Buying Treasuries Again

December 12, 2025This will note will get a bit more technical than some of our others – and it will be on the long side (apologies in advance). Nevertheless, it covers a topic that we think is important to address given the implications for the broader market.

As usual, if you do have questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out and ask.

You may have heard that the Federal Reserve announced that it will begin buying T-bills and Treasury securities with maturities under 3 years. This will be done on a monthly basis beginning today.

Now, you might think that this sounds awfully familiar to another policy measure in the Fed’s tool kit – quantitative easing (or QE). But it’s not. There are important differences between the ‘reserve management program’ (or RMP) and QE.

To break this down, we need to step back a bit - beginning with how the Fed actually implements its policy, how this influences the SOFR market and why the Fed is buying shorter-dated securities again.

How does the FOMC set the policy rate?

Whenever the FOMC sets policy (hikes or cuts rates), it isn’t done in a ‘fiat’ manner.

There are different interest rates (called administered rates) that it also changes to ensure that the effective Fed funds rate stays within the target range that it has proscribed. Mechanically speaking, the changes in these administered rates helps to influence the clearing rate for overnight unsecured loans between participants in the Fed funds market.

However, not everyone can participate in this market. Only institutions that have a certain type of money (called reserves) parked at the Federal Reserve can participate. This is a very narrow group that includes commercial banks, thrifts, US branches of foreign banks and government sponsored enterprises (GSEs).

Okay, but how does the Fed funds rate influence the SOFR market?

The SOFR market is where different counterparties can lend/borrow for as short a duration as overnight using US Treasuries as collateral (a transaction that is called a repurchase agreement or a ‘repo’). This is a much broader market than the Fed funds market and includes banks, GSEs, hedge funds, asset managers, and money market funds.

Did you notice something interesting yet? Indeed, a few of the participants in the Fed funds market (namely banks, GSEs) can also participate in the SOFR market as lenders. Because of this, the overnight SOFR rate and the Fed funds rate tend to track closely together (as wide spreads between the two would be arbitraged away).

Also, because overnight SOFR transactions are secured, the rate should theoretically be lower than the Fed funds rate. So when the Fed sets interest rates, the overnight SOFR rate helps to set the floor for short-term funding costs for the financial system.

But why did volatility increase in the SOFR market recently?

Remember that when the Fed allows a Treasury or mortgage-backed security to roll off its balance sheet (a process called quantitative tightening, or QT), somebody else in the financial system is buying it.

That implies that somewhere out there in the financial system, a deposit is burned. For commercial banks, that means a liability (deposit) is going down which also means that an asset (reserves held at the Fed) should as well. The Fed conducted QT for years before stopping on December 1st.

The continual process of QT effectively meant that reserves in the Fed funds system shrank as well. In fact, they got to a point where they were no longer ‘abundant’ but merely ‘ample’ (forgive us for the verbiage, but this is how the Fed refers to them). The problem with having ‘ample’ reserves is that it often may not be enough to ensure stability in the overnight funding markets.

For instance, once reserves had shrunk to ‘ample’ levels, some of the banks/GSEs that needed funding found that they couldn’t tap the Fed funds market and instead had to turn to the SOFR market. When enough banks did this, it led to a situation of relative cash scarcity/collateral abundance in the SOFR market. That meant higher than usual SOFR rates.

And remember, if SOFR rates are moving higher when the Fed is not actually hiking – it disrupts the process of monetary policy transmission. On Halloween, the spread between overnight SOFR and the Fed funds rate reached 36bps(!). That means the financial system effectively tightened despite the fact that the Fed had eased rates only a few days before.

This is where the Fed steps in…

By purchasing T-bills and (potentially) select coupons in the secondary market, the Fed is effectively increasing the amount of deposits held in the banking system. If we work backwards from the above steps, this means that reserves should increase in the Fed funds market and that the cash scarcity/collateral abundance in the SOFR market should normalize as well.

However, there are some periods when reserves will shrink temporarily. For instance, when households and businesses pay taxes. The Fed’s RMP program is also meant to be flexible enough (through changing monthly amounts that are focused on shorter duration securities) to anticipate these fluctuations. In turn, that should mean calmer SOFR markets.

But how is this different than QE?

The purpose of QE is to stimulate the economy when the Fed funds rate is close to zero. The Fed does this by buying large amounts of bonds (generally longer duration) in a sustained manner with the intent of lowering long-term rates and boosting credit creation to drive growth.

The purpose of the RMP is that it’s an operational measure meant to maintain enough reserves in the system to ensure that monetary policy is transmitted in an efficient manner. These are smaller, flexible purchases that are conducted as needed to offset reserve drains.

Importantly, RMPs are NOT tied to macroeconomic objectives. In fact, the Bank of Canada conducts similar actions for the same reasons.

Again, this has been a longer note than we anticipated. Nevertheless, we hope that by shedding light on the how and why, we can pre-empt any unfounded claims that the Fed’s actions this week are akin to QE.

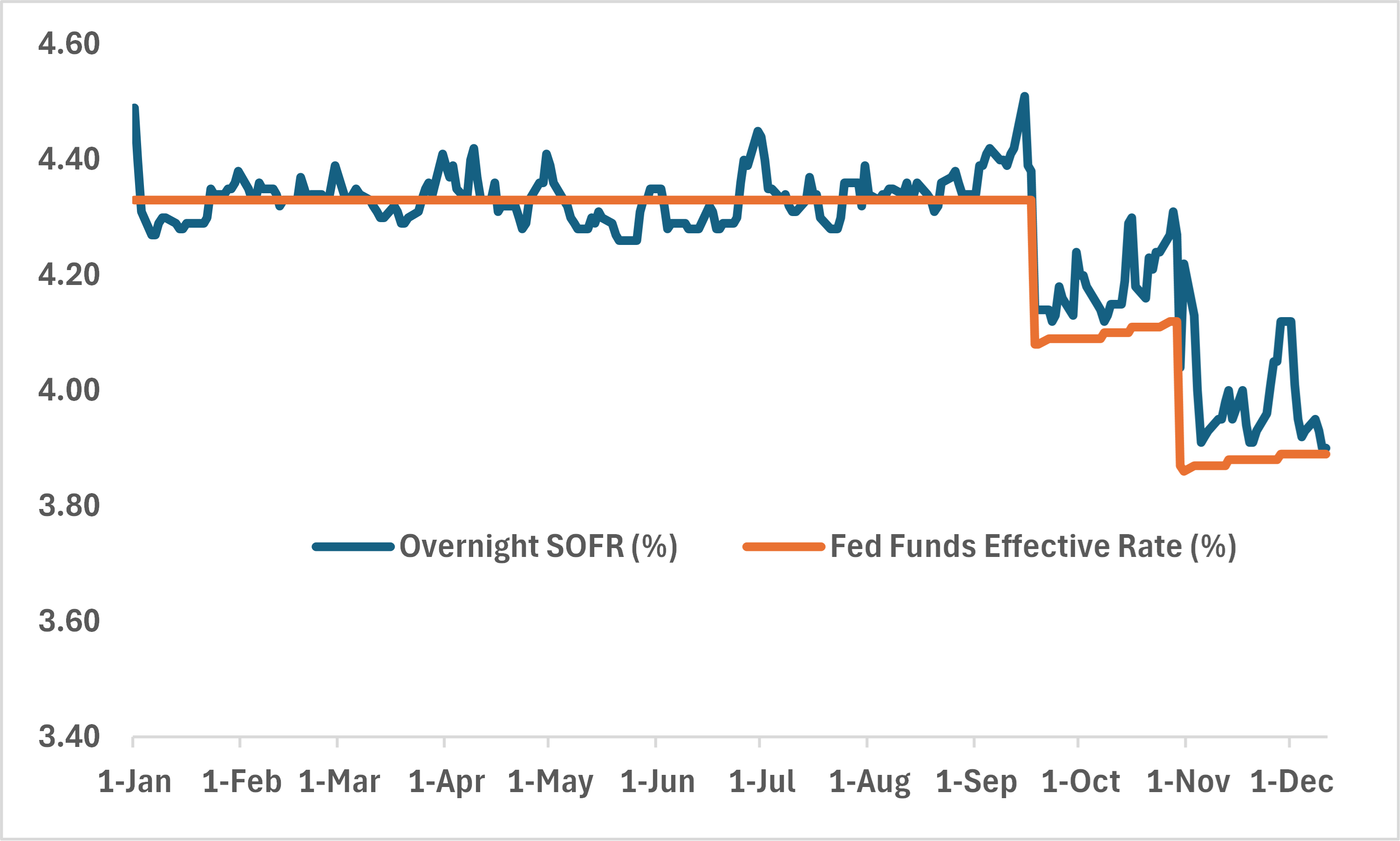

Chart 1 – Divergences Between Overnight SOFR and Fed Funds Effective Rate are a Problem for the Federal Reserve

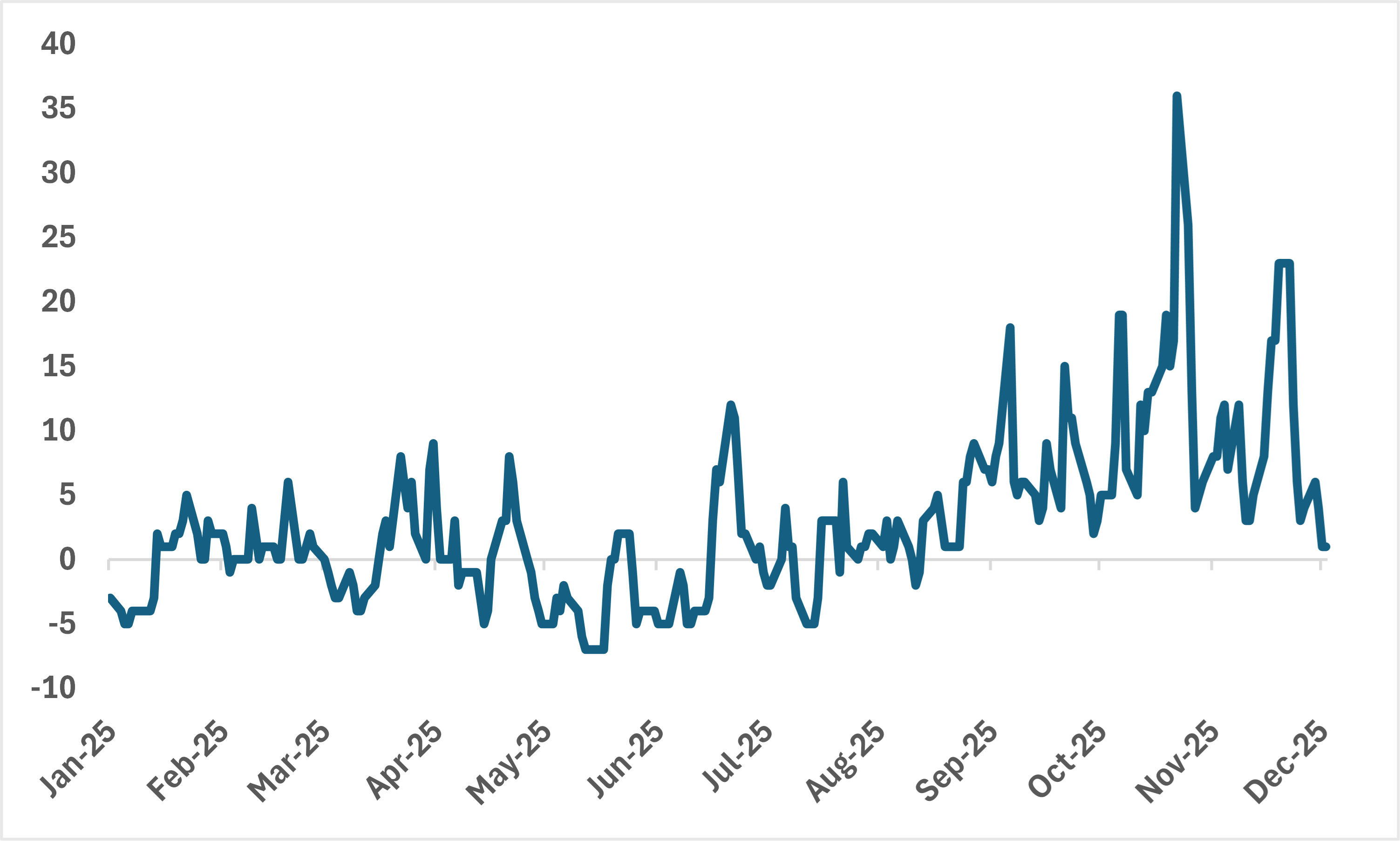

Chart 2 – Overnight SOFR – Fed Funds Effective Rate Spread (bps)

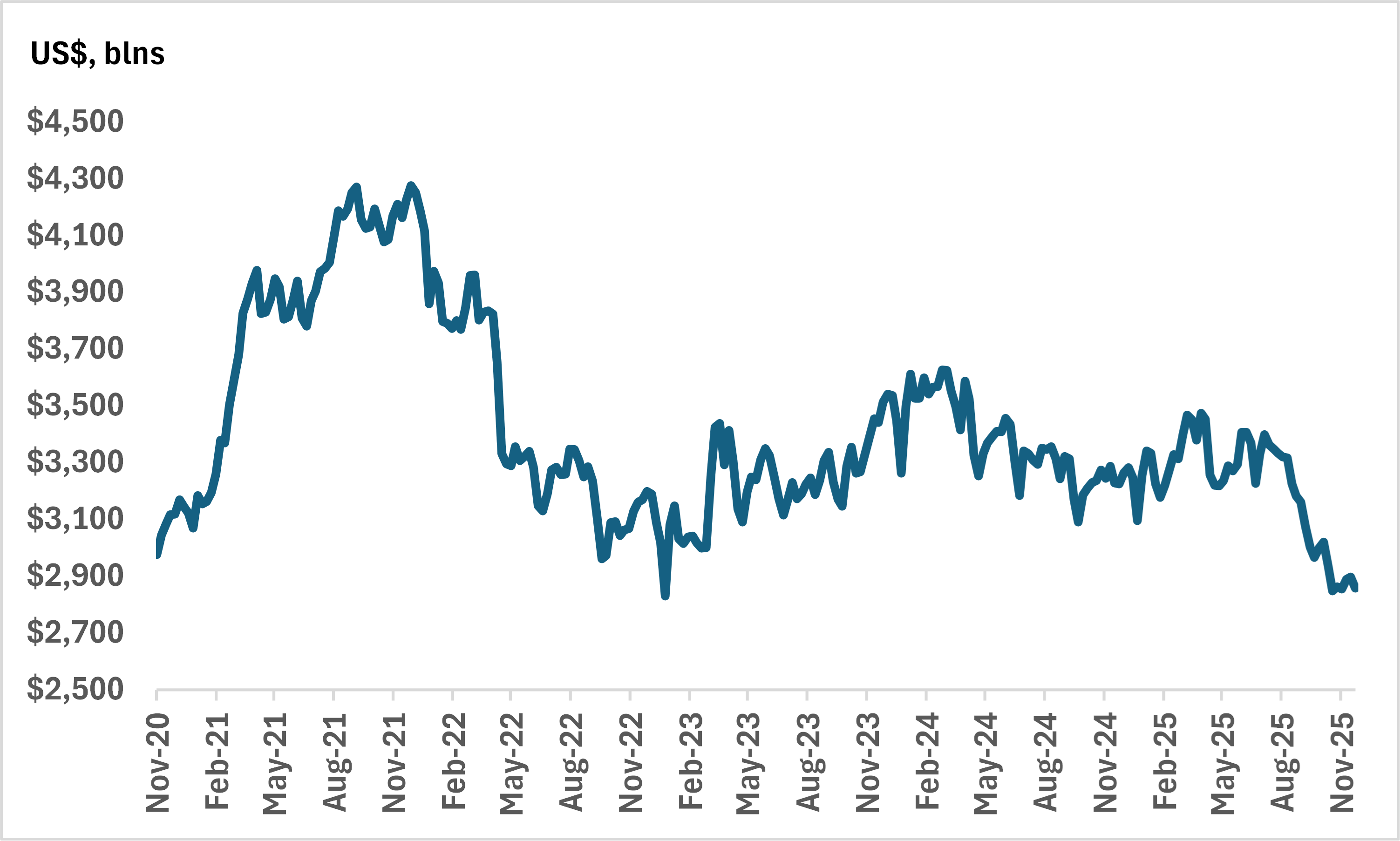

Chart 3 – Banking System Reserves Have Been Dropping…